That feeling when your battery bar flashes red to signal there’s 20% of juice left before your phone conks out is enough to send most of us into panic.

But what about when there’s just a smidge of a dip from full power.

When does that thump thump thump hit your heart… at 36%? 49%? 62%?

Or maybe even any number below 100%.

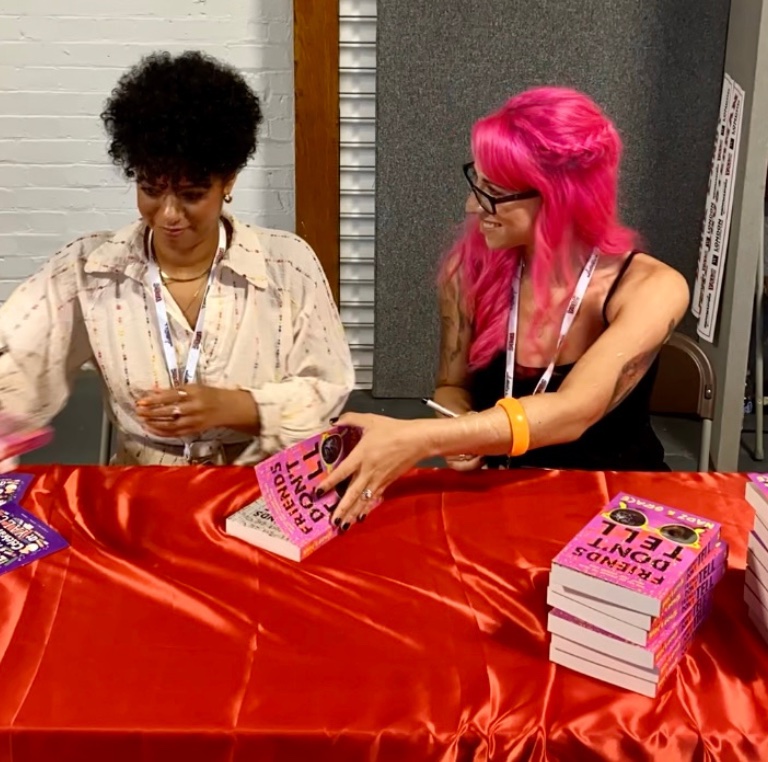

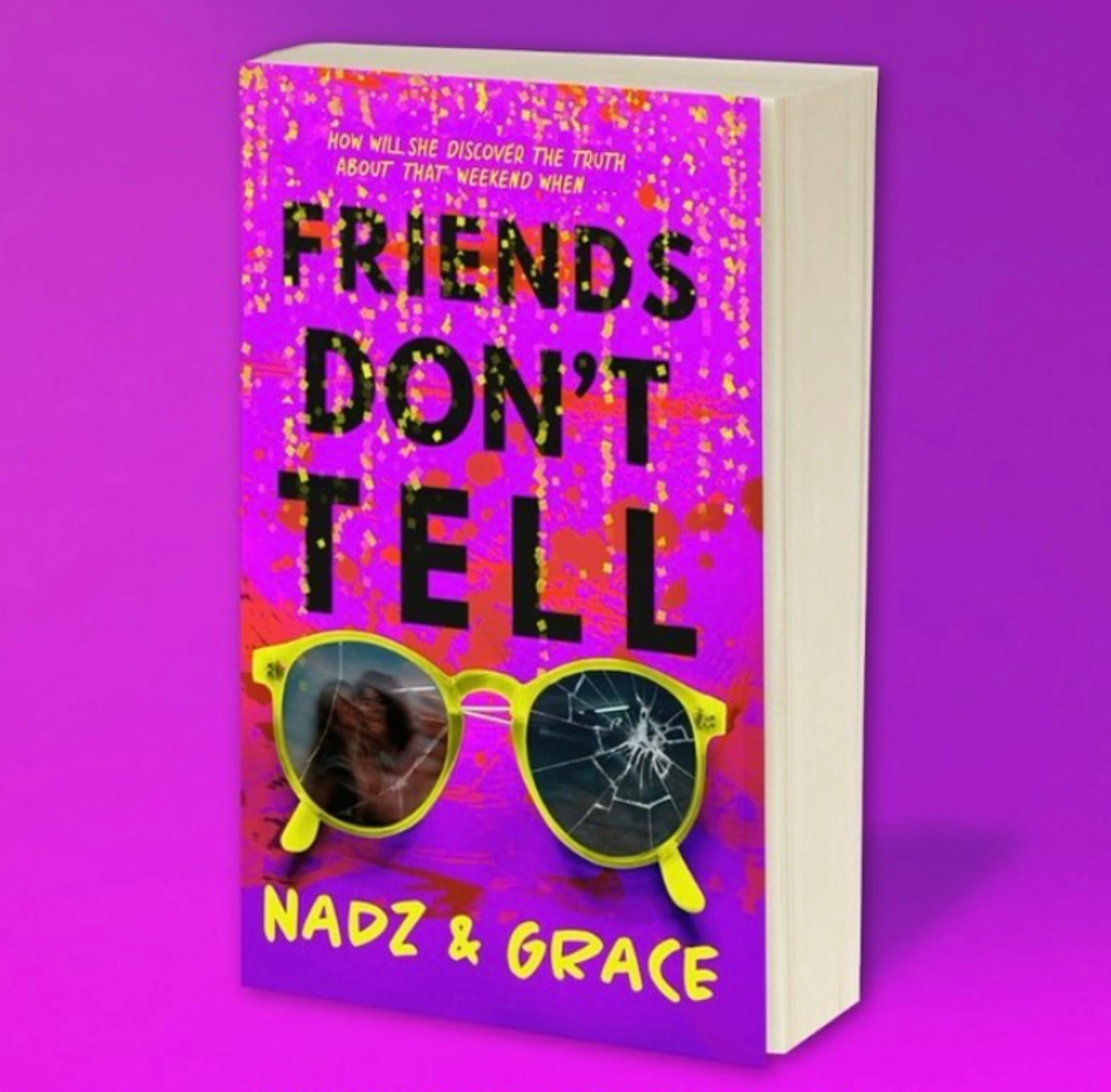

It sounds as ridiculous as it does impractical, so much so that when I wrote about a teen struggling with low battery anxiety in my new YA thriller Friends Don’t Tell, feedback from an early reader was to tone it down as ‘Lex’s panic over her phone not being charged seems very OTT’.

The suggestion was to tweak the story as it ‘might be more believable if she needed to keep it over 90%, keeping it at 100% is impossible – you’d have to keep it plugged in constantly.’

This is the reality my mum lived in though. Utterly consumed by these three digits. 100. Unless she saw them on the battery bar, panic spiralled.

She’d interrupt chats, meals, films, sleep, to make sure the phone was plugged in. There were times I thought we were deep in conversation, where I’d say something personal or important to me, and she’d reply with, ‘Is my phone plugged in?’ – her mind clearly elsewhere.

Not only was this immensely frustrating, but also heartbreaking as there didn’t seem to be a way to reason with her.

Although, ultimately, I think this is where I was going wrong…

While it seemed illogical, this is how mental health conditions present, without logic. I looked at her compulsions, trying to understand, when what I needed was a deep dive to unearth the root cause.

Just as I self-harmed as a coping tool, it wasn’t really the act of self-injury that kept me going back, but the unresolved emotions that led me there in the first place.

For mum, the impulses were exacerbated by her terminal illness, Progressive Supranuclear Palsy, which severely affects the problem-solving part of her brain.

Due to her deterioration, it made it easier to feed the addiction, sitting in a chair by the socket constantly. (Now, she’s unable to use her phone or move independently, so the obsession has by default dwindled.)

For others, unless you carry multiple power bars, 100% charge is a challenge that can never be achieved, which is what feeds into the anxiety itself.

In addition to this, behaviours often go unnoticed. In the same way we normalise excessive alcohol consumption and booze addiction slips under the radar, so too can phone obsession given that the majority of us are wedded to these mini computers that cannot love us back.

Many of us are clued up now about how our brains are addicted to notifications, that they release dopamine, a neurotransmitter responsible for motivation and pleasure, which is what triggers us to keep going back for more and checking, checking, checking.

Yet how – and crucially – why are more of us obsessed with battery charge too?

I spoke to Helen Jambunathan, Associate Insight Director at Canvas8 (global leaders in behavioural insights), who believes that low battery anxiety has become so prevalent because people’s emotional bonds to their smartphones are stronger than ever before.

Helen told me: “Anthropologists have started to think of smartphones as an extension of our actual homes – people have begun to live ‘in’ and ‘through’ their devices as much as they do in real life. Research shows that for many people, being on their phones evokes a powerful sense of ‘coming home’.

“The smartphone has become our nexus of connectivity, enabling us to express, connect, and explore. Because of this, it’s also a huge source of comfort and emotional security.”

This may explain why low battery is so anxiety-inducing, as it’s not just about running out of juice, but an intense fear of not being able to access your phone which represents a closing down of space.

Helen also said: “Smartphones provide a form of escape and ability to take us out of situations we find ourselves in, like awkward social engagements or periods of boredom.

“Smartphones act as a sort of ‘adult pacifier’. There is going to be anxiety when the battery is low and we’re about to lose that. And the more dependent a person is on their device, the stronger effect low battery anxiety is likely to have.”

In the UK, 71% of people claim to never turn their phone off, while 78% say they could not live without it. Meanwhile, the average Brit picks up their device every 12 minutes!

Jambunathan added: “Studies suggest that smartphones become key signifiers of identity – perhaps because people are so attached to them. Some see phones as an extension of themselves, which means that there is a desire for devices to reflect their personality.

“If part of ourselves is going to ‘die’ (when battery runs out), we’re going to be anxious about it.”

I also interviewed Psychologist and Wellbeing Strategist, Kasia Richter, who says behind these behavioural addictions lie loneliness, low self-worth, and not being seen, heard, or loved.

These are fundamental human needs that require nurturing to thrive, and without them, we become detached from our peers and more inclined to connect online.

Kasia said: “Often, mobile addiction develops as a way of running away from problems, a distraction of what we need to explore, when what we require is attention, support, and to talk without judgement.”

This heavy dependence on smartphones is now reshaping brain development for future generations, where there is an increased lack of ability to create certain neuro pathways.

Richter continued: “Low battery anxiety, similarly to nomophobia (the fear of being without your phone), is particularly widespread amongst those who have grown up with mobiles.

“The smartphone has affected most aspects of their functioning, for example, relying on Google Maps so brains do not develop in the same way as people who learned to use maps.

“If your brain lacks special memory, and you didn’t develop navigating skills, then being in town without back-up (your phone) or running low on battery can generate genuine fear.”

Dr Elena Touroni, a consultant psychologist and co-founder of The Chelsea Psychology Clinic, supports the notion that we use our phones to feel connected – to others and the world more widely.

Consequently, this creates a certain level of dependence, which can lead to anxiety and a feeling as though we won’t be able to cope with being out of touch if our battery drops.

She also believes compulsions may be part of a bigger psychological issue, depending on an individual’s own underlying vulnerabilities.

Touroni said: “If someone uses their phone primarily as a distraction or to self-soothe, low battery can be the removal of an important coping mechanism.

“Alternatively, a person might rely on their phone to feel connected and so no charge may spur on anxiety related to feelings of disconnection. The type of anxiety it provokes will have a lot to do with a person’s own vulnerabilities as well as the relationship they have with their phone.”

For me, this insight helps enormously when the go-to response could be annoyance or anger to see mum incessantly on her phone when she was surrounded by loved ones IRL.

Instead, if we approach with empathy and compassion, to recognise a phone’s power in connecting people rather than a piece of tech with no heartbeat, then suddenly those who struggle to cope without their handsets no longer seem ‘rude’ but in need of attachment.

For anyone struggling with low battery anxiety, Smriti Joshi, Lead Psychologist at Wysa (an emotionally intelligent AI chatbot), said there are ways to stay cool in a crisis.

Notably, Joshi encourages you to train yourself to be without your device so that should it happen unpredictably, you feel safe.

She says: “Have some no-device time every day where you deliberately don’t carry your phone with you. Start with 10 minutes and work up to at least 30.

“Use this time to be mindful of surroundings, connect with yourself, using your breath to anchor you in the moment. This will help you feel relaxed and calm. Go for short walks without your phone.

“Remind yourself that you’re not going to miss out on anything important if you check your phone occasionally, rather than every few minutes. We’ve all been in situations where we keep checking our phone for an update from someone, yet nothing changes for hours.”

Joshi also suggests spending time with people in-person to reduce emotional dependency on your device; carrying important phone numbers on you in an old school format so that if you do run out of power, you can still reach people in an emergency; and speaking to a professional if your worries feel overwhelming or trigger intense panic.

Grab your copy here: Friends Don’t Tell.